Rehabilitation or risk? Public split on MOE's decision allowing accused students to take SPM

The complex debate over SPM access for students accused of gang rape

SHAH ALAM – The right to education must remain intact regardless of a person’s legal status, say some child rights advocates, following a public debate over whether students accused in a criminal case should be allowed to sit for their Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM) examinations.

Others, however, argued that the right to education must not override the safety and well-being of the victim and other students.

Child rights activist and former Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (Suhakam) commissioner Dr James Nayagam said education should continue independently of any trial, verdict, or allegation, as it forms a key part of personal growth and rehabilitation.

“In 2004, I started the first school in Kajang Prison for juvenile inmates. Among my students were boys charged with serious offences, including murder and rape.

“Those who were given the opportunity to continue their studies up to SPM, Sijil Tinggi Persekolahan Malaysia (STPM), and even university have since been released and are now leading normal lives,” he told Sinar Daily.

Nayagam stated that this principle had long been upheld, recalling the initiative to introduce formal education for juvenile inmates in Kajang Prison.

The initiative, he said, enabled many young offenders to complete their studies and successfully reintegrate into society upon release.

He stressed that education and justice are separate matters that must not be conflated.

“The outcome of a trial has to be determined in court, but education is a lifelong process that should not be disrupted. We cannot punish through education even before someone is proven guilty,” he said.

Nayagam added that minors accused of crimes still deserve due process and protection from stigma, with their identities safeguarded even as they face the justice system.

He argued that concerns about safety or trauma could be addressed by arranging separate exam venues under supervision.

“Education is education wherever they are, whether in prison or outside, it carries on. But justice also has to be seen to be done, and it takes a different thing, and we have to wait for the outcome of that,” he said.

Safety vs Educational Rights: The Counterargument

Meanwhile, child activist Datuk Dr Hartini Zainudin said while education is a right, it should not override the need to ensure safety and a trauma-free environment for all students.

“We’re comparing apples to oranges. The right to education is not the same as the right to safety and justice.

"The state’s first duty is to protect the victim and ensure a safe, trauma-free school environment,” she said.

Hartini said allowing the accused to take exams in the same school could risk re-traumatising the survivor and sending the wrong message to others.

She suggested that a balanced approach was necessary; one that upholds due process while prioritising protection.

“A separate, supervised exam location is a fair compromise; it upholds both due process and protection,” she added.

She highlighted that true education includes moral and social responsibility and the system must not normalise harm by allowing accused individuals to continue schooling “as normal” without consideration.

The controversy stems from an alleged gang rape of a 15-year-old Form Three student by senior male students in a classroom last week.

The incident was reportedly recorded on a mobile phone. All four suspects have been remanded, but are scheduled to sit for their SPM exams beginning Nov 3.

Education Minister Fadhlina Sidek confirmed the decision, stating that while the police investigation continues, the students' right to sit for their exams will be preserved in line with the principle of "education for all."

The ministry’s current focus, she added, is ensuring all students and teachers at the school receive full emotional and psychosocial support.

The victim remains in hospital receiving treatment and psychological counselling.

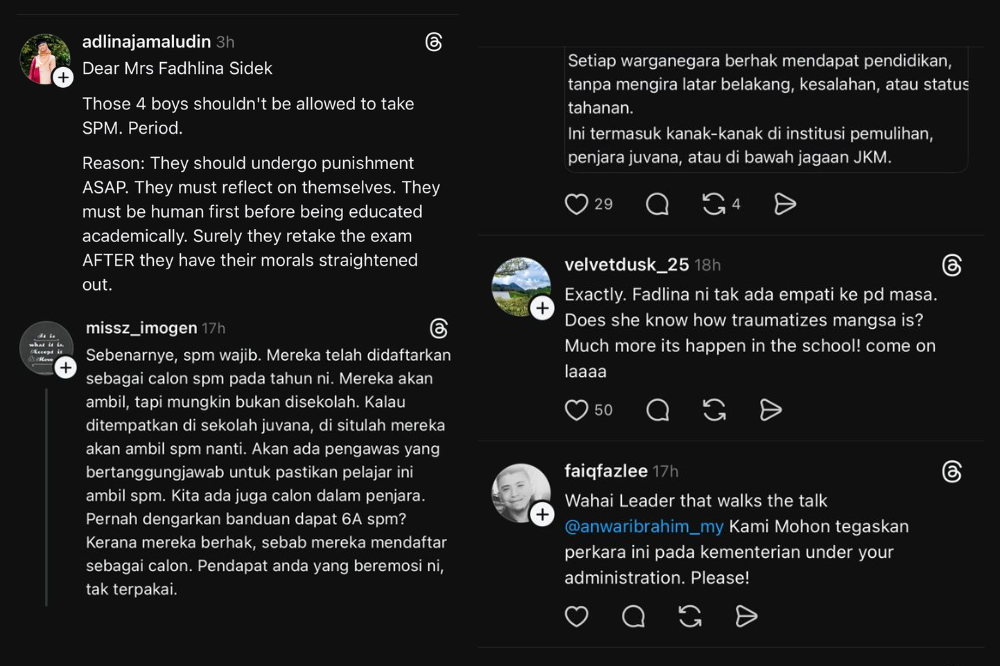

The issue has triggered intense and emotional discussion online, revealing a deep split in public opinion.

On one side, many argue that moral accountability should take precedence.

User @adlinajamaludin garnered significant support, stating: “Those 4 boys shouldn't be allowed to take SPM. Period. They must be human first before being educated academically. Surely they can retake the exam AFTER they have their morals straightened out.”

This comment received over 10,000 likes, sparking a heated thread below it.

Many echoed this sentiment, focusing on the victim's trauma. @velvetdusk_25 replied, “Exactly. Does the Minister have any empathy for the victim? Does she know how traumatised the victim is?”

Conversely, a significant number of users defended the decision based on legal principles and rehabilitation.

@mahirahazemi countered, “As much as we all want justice, we can’t deny the right of the 4 boys to take SPM as per the Juvenile Justice system. I suggest you do some reading before making such statements.”

Further reinforcing this view, @lvckrmn pointed to the philosophy behind the law: “Allowing juvenile offenders to sit for SPM is part of Malaysia's justice system and reflects a rehabilitative, rather than purely punitive, approach. It's guided by the Child Act 2001.”

Download Sinar Daily application.Click Here!